In the previous instalment, I spoke a little about issues companies face in their content management practice as related to information security and integrity. In part 2, I’m picking up where I left off, airing more dirty laundry – I mean content issues – we are all likely to run into at some point.

I ended part 1 with a discussion of information integrity: how it becomes so ridiculously easy in the typical traditional space to end up with duplicate files everywhere and no way to establish which one is the single version of the truth. Well, this next one leads to the same end result, albeit by a slightly different path:

Version control and Document Lifecycle Management

Even if you’ve managed to side-step the Adventures of Spartacus, you’re not quite out of the woods yet. Even if you have the most disciplined users in the world and you can guarantee you have no duplicate folders / documents, you still have to deal with the barrel of laughs that is version control.

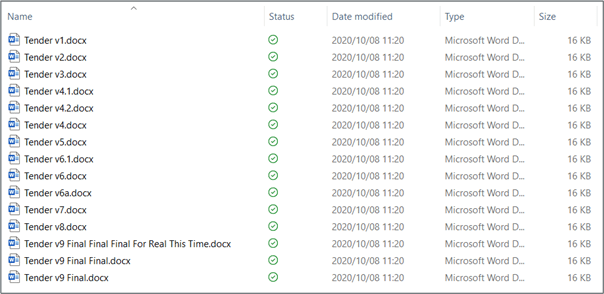

While SharePoint does natively support 2 different forms of version control (assuming you’ve enabled it), network drives absolutely do not. So, if you’re blessed with a traditional network shared drive, the only hope you have of maintaining some level of version control integrity is to create a new copy of your document with every change:

Spot the problem? Problem(s), I should say.

If a user forgets to copy the last version of the document before starting, you’re stuck – the last known good version of the document has just been overwritten. Good luck recovering from an oopsie now.

- If two users try to perform edits at the same time, you’re stuck – someone’s going to end up overwriting someone else’s changes or making updates based on a version which is no longer current.

- If someone accidentally copies a non-current version and edits that, you’ve lost all the more recent versions in between.

- And last but not least, BLOAT. Massive storage waste. If you have 20 versions of a 1MB document, you are now using 20MB of space to store it. Extrapolate that across an entire department over a year. I know the price of storage has fallen dramatically in recent years, but at this kind of exponential growth, there is simply no way to effectively manage the expansion that goes with it.

There’s just no elegant way around this unless you’re using a platform specifically designed to effectively manage version control.

Governance and Regulatory Compliance

For me, 2001 was one of those pivotal years where everything changes, both personally and professionally, but it would be years before I was able to properly understand the full impact it would have on me from a career perspective.

First there was 9/11. Then there was the Enron scandal in December of that same year. Two events on the far side of the globe that sent shockwaves through the international community for vastly different reasons. They had one huge thing in common, though: they forever changed the way we do business.

2002 saw the introduction of Sarbanes-Oxley, a set of regulatory standards intended to support good governance and transparency which all publicly traded companies were expected to abide by. SOX introduced new requirements for document generation, storage, and retention, as well as the processes by which all of these standards were to be managed. I remember my employer at the time grappling with the scope of the thing – it was going to take millions to implement and cause massive disruption in overall business flow.

2004 (or was it 2005?) saw the introduction of anti-money-laundering and terrorism prevention (AML) legislation world-wide. It just so happens that I was employed to provide project administrative support for a major international bank’s AML rollout to all their subsidiaries on the African continent. Again, there was the sense of shock, not only at how much this was going to cost, but what it was going to mean in terms of process overhead.

Many companies approached requirements such as these by making it someone else’s problem: throw money at some third-party product / service provider that will guarantee their shiny new toy will solve all the client’s problems – at least that way, they had some plausible deniability. It was open season on business and sadly, some companies did fall prey to grifters and con artists along the way.

Of course, that’s not the whole story – what fun would that be? HIPAA has governed the management of personal medical information since 1996. The Basel Accords have governed banking and financial services, starting with Basel I in 1988, followed by Basel II in 2004, and Basel III in the wake of the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008. And yes, you’d better believe it, the first steps towards the implementation of Basel IV started in January 2022. And I haven’t even started on health and safety compliance standards in the construction and mining industries, etc., but I think you’re starting to get the picture.

Prepare for Changing Regulations

My point is that while standards and the processes that support them are essential to good governance, more often than not, each new standard (and its associated processes) brings with it at the very least some requirement for documentary evidence of compliance. That documentation must be generated, stored, shared, secured, curated, retained, and eventually disposed of according to highly detailed requirements. As I mentioned earlier, organizations have often simply gone to market for the shiniest tool they could afford to handle this latest requirement, but when competing standards (and tools) seek to manage the same compliance documentation in different ways for different purposes, how do our (now competing) tools resolve that conflict? Even though after 20 years the pattern of behaviour is clear, it seems to me most organizations are still woefully unprepared for when the Next Big Requirement comes along.

What’s the golden thread that binds all of these events together? While we know change equals pain, every time a new regulatory requirement is published or a new framework is released, organizational pain is multiplied exponentially for one reason:

For most companies, content management has never been seen as having corporate strategic value, so it has never been prioritised as such. As a result, hap-hazard management of documentation is the rule rather than the exception, further complicating the implementation of multiple standards on the same content base. Any enterprise hoping to simplify and streamline the adoption of new standards in the future must address the underlying issue first: how best to store, identify, curate, manage, and eventually dispose of the documentation they already have in such a way that changing regulations are absorbed and implemented with as little disruption as possible.

In the next instalment, I’d like to explore content management from a strategic perspective, content management as a discipline, and how that discipline brings us just a smidgeon closer to our end goal.